Rust Never Sleeps, 1979

For anyone still passionately in love with rock & roll, Neil Young has made a record that defines the territory. Defines it, expands it, explodes it. Burns it to the ground.

Rust Never Sleeps tells me more about my life, my country and rock & roll than any music I've heard in years. Like a newfound friend or lover pledging honesty and eager to share whatever might be important, it's both a sampler and a synopsis—of everything: the rocks and the trees, and the shadows between the rocks and the trees. If Young's lyrics provide strength and hope, they issue warnings and offer condolences, too. "Rust never sleeps" is probably the perfect epitaph for most of us, but it can also serve as a call to action. On 1974's On the Beach, the singer summed up a song ("Ambulance Blues") and a mood with the deceptively matter-of-fact phrase, "I guess I'll call it sickness gone." On that same LP, he felt such a renewal of power that he delivered, in "Motion Pictures," what may be the most boastful and egotistic line in all of rock & roll: "I hear the mountains are doing fine." Rust Never Sleeps makes good on every one of Young's early promises.

As you can see, we're dealing with omniscience, not irony, here. Too often, irony is the last cheap refuge for those clever assholes who confuse hooks with heart, who can't find the center of anything because their edges are so fashionably fucked up, who are just too cool to care or commiserate. Neil Young doesn't have these problems. Because he actually knows who he is and what he stands for, because he seems to have earned his insights, because his idiosyncratic and skillful music is marked by wisdom as well as a wide-ranging intelligence, Young comes right out and says something—without rant, rhetoric, easy moral lessons or any of the newest production dildos. He doesn't need that crap. This man never reduces a song to the mere meaning of its words: he gives you the whole thing, emotions—and sometimes contradictions — controlled but unlimited. For my money, Neil Young can outwrite, outsing, outplay, outthink, outfeel and outlast anybody in rock & roll today. Of all the major rock artists who started in the Sixties (Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones, the Who, et al.), he's the only one who's consistently better now than he was then.

Though not really a concept album, Rust Never Sleeps is about the occupation of rock & roll, burning out, contemporary and historical American violence, and the desire or need to escape sometimes. It's an exhortation about coming back for those of us who still have that chance — and an elegiac tribute to those who don't. That much is pretty clear. But unlike most of Young's records, this one's a deliberate grab bag of styles, from sensitive singer/songwriter seriousness ("Thrasher") to charming science fiction ("Ride My Llama") to country rock ("Sail Away," a gorgeous Comes a Time outtake sung with Nicolette Larson) to an open embrace of the raw potency of punk (the hilarious and corrosive social commentary of "Welfare Mothers"). Side one is awesomely acoustic: ostensibly a folkie showcase, it's actually a virtuoso demonstration of how a rock & roller can switch off the electricity and, through sheer personal authority and force of will, somehow manage to increase the voltage. Side two is thunderous Crazy Horse rock & roll, but its opening song, "Powderfinger," is, oddly enough, the LP's purest folk narrative. And, to prove that he's more than just a contender, Young punches out one tune, "My My, Hey Hey (out of the Blue)" or "Hey Hey, My My (into the Black)," both ways.

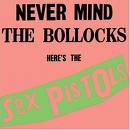

Rust Never Sleeps leads off with "My My, Hey Hey (out of the Blue)," and you can tell in an instant—by those haunted, ominous low notes played on the bass strings of the guitar, by the singer's respectful and understated vocal, by the lyrics' repetition—that this song lies not far from the heart of the matter. The heart of the matter here is death and desperation. And commerce. While "out of the blue and into the black" is a phrase that's filled with mortal doom, "into the black" can also mean money, success and fame, all of which carry a particularly high price tag. "My my, hey hey," Young sings, the line both fatalistic and mocking, "Rock and roll is here to stay." Elvis Presley and the Sex Pistols are introduced:

The king is gone but be's not forgotten

This is the story of a Johnny Rotten

It's better to burn out than it is to rust

The king is gone but he's not forgotten.

Though Young believes "Rock and roll can never die," he knows that a lot of people in it can—and do. Fast. Hence, the final admonishment: "There's more to the picture/Than meets the eye."

The autobiographical "Thrasher" (the threshing machine as death symbol) follows, and it's about rock & roll destructiveness, too—this time in the guise of the easy living that can lead to artistic stagnation. But even as the singer chronicles the downfall of many of his friends and fellow musicians

They had the best selection, they were poisoned with protection

There was nothing that they needed, they had nothing left to find

They were lost in rock formations or became park bench mutations

On the sidewalks and in the stations, they were waiting, waiting

he makes the decision that it won't happen to him: "So I got bored and left them there, they were just deadweight to me/Better down the road without that load."

Written partly in the florid and flowery style of mid-Sixties rock "poetry" and beautifully played on the twelve-string guitar and harmonica, "Thrasher" is a very complex composition that dwells deeply on the ties and boundaries of loyalty, childhood memories, fear, drugs, the music business, taking a hardheaded stand and art itself. When the latter is threatened, Young sings:

It was then that I knew I'd had enough, burned my credit card for fuel

Headed out to where the pavement turns to sand

With a one-way ticket to the land of truth and my suitcase in my hand

How I lost my friends I still don't understand.

If those lines remind you of the "On the Beach"/"Motion Pictures"/"Ambulance Blues" side of On the Beach, they're supposed to. That song cycle was also about survival with honor.

Taken as a unit, "My My, Hey Hey (out of the Blue)" and "Thrasher" almost suggest a paraphrase of the frontier father's warning to his son in side two's "Powderfinger": rock means run, son, and numbers add up to nothin'. But Young isn't that preachy. If he's strong enough to leave, he's strong enough to stay and work, too. He's able to adapt ("I could live inside a tepee/I could die in Penthouse thirty-five"). He'll bury his dead and maybe even drop a ghastly joke about it: "Remember the Alamo when help was on the way/It's better here and now, I feel that good today." Though his profession may be dangerous, it can also be glorious, and in the end, he's proud of it ("Sedan delivery is a job I know I'll keep/It sure was hard to find"). With Crazy Horse in Rust Never Sleeps' ferocious finale, "Hey Hey, My My (into the Black)," Neil Young makes rock & roll sound both marvelously murderous and terrifyingly triumphant as the drums crack like whips, the guitars crash like cannons and the vocal soars above the blood-red din like the flag that was still there. "Is this the story of Johnny Rotten?" the singer asks. Yes and no. If we can't beat it, we can sure as hell beat it to death trying, he seems to be saying.

I'd be the last person in the world to claim that "My My, Hey Hey (out of the Blue)"/"Hey Hey, My My (into the Black)" and "Thrasher," two of the album's best tunes about rock & roll, have any direct connection with "Pocahontas" and "Powderfinger," Rust Never Sleeps' pairing about America. Of course, I'd be the last person in the world to deny it, too.

"Pocahontas" is simply amazing, and nobody but Neil Young could have written it. A saga about Indians, it starts quietly with these lovely lines

Aurora borealis

The icy sky at night

Paddles cut the water

In a long and hurried flight

and then jumps quickly from colonial Jamestown to cavalry slaughters to urban slums to the tragicomic absurdities of the present day:

And maybe Marlon Brando

Will be there by the fire

We'll sit and talk of Hollywood

And the good things there for hire

And the Astrodome and the first tepee

Marlon Brando, Pocahontas and me.

With "Pocahontas," Young sails through time and space like he owns them. In just one line, he moves forward an entire century: "They massacred the buffalo/Kitty corner from the bank." He even fits in a flashback—complete with bawdy pun — so loony and moving that you don't know whether to laugh or cry:

I wish I was a trapper

I would give a thousand pelts

To sleep with Pocahontas

And find out how she felt

In the mornin'on the fields of green

In the homeland we've never seen.

Try reducing that to a single emotion.

Like the helicopter attack in Francis Coppola's hugely ambitious Apocalypse Now, the violence in "Powderfinger" is both appalling and appealing—to us and to its narrator—until it's too late. In this tale of the Old West, a young man, left to guard a tiny settlement, finds himself under siege and can't help standing there staring at the bullets heading his way. "I just turned twenty-two/I was wonderin' what to do," he says. Between each verse, Neil Young tightens the screw on his youthful hero with some galvanizing guitar playing, while Crazy Horse cuts loose with everything they've got. The tension is traumatizing, our empathy and fascination unbearable. And Young refuses to let us look away.

"When the first shot hit the dock I saw it comin'," the boy says. We hang with him. And underneath the lyrics (in critic Greil Marcus' classic description), there's "that string of ascending [guitar] notes cut off by a deadly descending chord — fatalism in a phrase." The hero acts: "Raised my rifle to my eye/Never stopped to wonder why." Young pulls the trigger. The narrator says: "Then I saw black and my face splashed against the sky."

The song doesn't even end there. Instead, the dead boy adds another verse:

Shelter me from the powder and the finger

Cover me with the thought that pulled the trigger

Just think of me as one you never figured

Would fade away so young

With so much left undone

Remember me to my love, I know I'll miss her.

The king is gone but he's not forgotten. This, too, could be the story of a Johnny Rotten. Hey hey, my my. Rock & roll can never die.

Neil Young should have the final word on his music, his future and Rust Never Sleeps. These lines from "Thrasher" make a magnificent credo:

But me, I'm not stopping there, got my own row left to hoe

Just another line in the field of time

When the thrasher comes I'll be stuck in the sun like the dinosaurs in shrines

But I'll know the time has come to give what's mine. (RS 302)

PAUL NELSON

===

More info on Paul Nelson at http://rockcritics.com/features/paulnelson-links.html